On my first day of service at the Haven House, a transitional housing program for homeless women and children, the social worker put her hand on my shoulder and said, “They’re tough girls, but I think you can handle yourself. Don’t let them scare you away. They might actually like this.”

On my first day of service at the Haven House, a transitional housing program for homeless women and children, the social worker put her hand on my shoulder and said, “They’re tough girls, but I think you can handle yourself. Don’t let them scare you away. They might actually like this.”

And by “this,” she meant writing poetry.

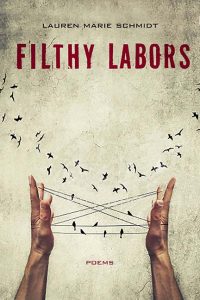

Comments like the social worker’s and questions like, “You’re an English teacher, why don’t you teach these girls how to really read and write?” inspired a sequence of poems in my most recent collection, Filthy Labors.

The women were not intended to stay longer than a year at the Haven House, 14 months at a maximum, but the vast majority of the women I worked with either stayed there for much longer or left and came back. I only remember a single case of a woman who made it out of the program entirely, but I can’t say for certain what kind of job she took. The idea was that the women who came to the Haven House would enroll in an education program, funded by the organization, that would earn the women some kind of skills-based certificate and, ultimately, a job that would get them back on their feet.

But the truth was that not all of the women were high school educated, and those who were, lacked sufficient enough reading and writing skills, not to mention job experience, to be successful in anything but a retail job, which is what almost all of them ended up doing. The reality is that any educational program that could make a difference to a single mother’s future—whether it’s cosmetology or culinary arts or phlebotomy, or radiology, or paralegal studies, or early childhood education—requires a high school diploma for acceptance and, in many cases, more than a single year to complete. Perhaps it is worth noting that the Haven House closed its doors in 2016 and the last pictures of the organization included one woman I remember working with when I left two years earlier.

***

A few times leading up to and including the day I started there, I was literally warned by the staff not to be put off by the women’s lack of respect towards authority figures. Of course, I wasn’t an authority figure and I didn’t want to be perceived that way. Knowing that the women were primed to dislike me based on their experience with the staff, in our first workshop, I mostly just listened to the women. I introduced myself and told them about my teaching background and things like that, but I said that I really wanted to make this something for them, that this workshop space wasn’t about me. And I said that the only way to do that, to create a safe space, is to earn their trust. So I invited them to ask anything they wanted to know about me—I mean anything.

And boy, did they ask me questions! One of the poems, “The English Teacher Gets a Lesson in Inference,” is about one such question:

The English Teacher Gets a Lesson in Inference

The Haven House for Homeless Women and Children

You got any kids? Dionna asks.

No, I say, I don’t have any kids.

You ever been pregnant?

I don’t have any kids, so…

That ain’t the question

that I asked you, she says.

Then she folds her arms across her chest

and waits for me to answer.

But they asked me everything from whether or not I’ve slept with women, to if I have or want kids, to if I’ve ever done drugs, to if I’ve ever been in a fight, to what is my family like, to why I became a teacher… and on and on. They grilled me. And the more open and honest I was, the more deeply they went with their questioning.

I ended the first session with a writing prompt about their names, where their names came from, what their names mean, things like that. In the poem “Expectations,” one of the women, named Brittany, wrote about how her mother gave her a “white girl name.” The poem uses snippets of what Brittany wrote in her journal about how people don’t see her as a Brittany:

Expectations

The Haven House for Homeless Women and Children, New Jersey, 2013

for you, Brittany

In your journal you write, My mama say she gave me a white girl name,

so I could one day get a good job and have a better life than hers.

My mother wanted to name me Donnaire or Arleen—

Donnaire because she heard the name once and loved it,

Arleen because her then best friend was Arleen.

For a time before I was born I was a Laura

like my great-grandmother, who laughed through her nose

and ate lemons, she said, so she could live until

she was a hundred. Laura died at ninety-four.

But when I came into the world, my mother’s

obstetrician proposed Lauren, and my parents signed the name

to my certificate. They signed both their names on either side.

My mother said she knew exactly when she conceived me,

as if I were a dream she made up with her own body, as if

she willed me here, her little girl. I imagine the two of them—

my father, twenty-six with two sons, two jobs, tired from

tending bar, lying with his wife in bed, stroking the half-basketball

beneath her cotton nightie, and my mother hugging the underside

of her belly, beaming at her high school sweetheart husband.

I imagine the two of them breathing me into being, each saying

I hope she has your eyes or Definitely, your sense of humor,

assigning to me the best they see in themselves.

Instead, your mother named you Brittany, trying not to see

the food stamps, the too-thin walls, and the empty side

of her bed. In Brittany, she saw an aunt and a grandmother,

on the night of your birth, get trapped in a department store

buying you dresses—too busy holding up tiny plastic hangers

with pink frills and white flowers, too busy cooing to note

that the store had already closed. In Brittany, she saw a baby girl

who took nearly three years to walk because nobody in the family

could bear to put her down. She saw birthday cakes, graduations,

a big white wedding where your father would give you away.

Today, a mother now, you write that people will never see you

as a Brittany. They say

you’re more Latasha or Danisha,

more Aiyesha or Kianna,

more Shirelle or Shonda. They say

you’re more Latoya than Lily,

more Deondra than Brianna,

more Kadijah than Courtney.

But you, Brittany, you say,

If they don’t expect me

to be what I am,

I’ll blow they minds

in more ways than one.

***

Over the course of the two years I was there, the nature of our meetings changed dramatically. We had gotten off to a strong start, but when we really got going, the women called it “class.” If they weren’t allowed to attend either because their child was sick or they had an appointment with DYFS (the Division of Youth and Family Services), they would report to me and say, “I have to miss class today, but give me my journal so I can do the prompt.” They called it “class”!!! Funny how originally, I didn’t want it to feel that way, but in their eyes, the space we’d created together was like a class. And it kind of was! Sometimes, we didn’t read or write poetry at all. There were weeks where I’d bring in short stories or articles. I showed them documentaries and we read excerpts of and watched Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun.

I took them to see two plays in my time there, too: Topdog/Underdog by Susan Lori Parks and August Wilson’s Two Trains Running. I called up Two River Theater Company in Red Bank—I lived on the same street as the playhouse in those days—and asked for free tickets. And I got them. Here is a poem that recounts our visit to Two River:

Ladies’ Day at the Playhouse

Two River Theater Company, Red Bank, New Jersey, February, 2012

MEMPHIS: You born free. It’s up to you to maintain it. You born with dignity and everything else…. Freedom is heavy. You got to put your shoulder to freedom. Put your shoulder to it and hope your back hold up.

—August Wilson, Two Trains Running, Act I, scene ii

For the Mothers of the Haven House for Homeless Women and Children

Hands grip painted rails as bodies and bodies climb

shallow stairs, file into to aisles, thin out into row

after row, after row like insects swarming a velvet maze.

The mothers pinch their tickets, show them to usher the way

children hold up a hall pass to a teacher—proof of their

belonging there. The late-sixties fixed as if behind museum glass,

a diner in Pittsburgh’s Hill District stands still on stage:

a counter, stools, tables and chairs, a payphone,

two booths, and a blackboard chalked with the menu.

We found our seats, eleven women split between two rows,

five in J, six in K, the bunch of us divided, but clumped together.

The mothers in back tugged on our hair, tickled our ears, pulled

the necklines of our sweaters. They snapped selfies with their cell phones—

seats, set, and stage captured in the background—

and made megaphones and telescopes with their playbills.

The house lights so silver-bright the room felt almost holy.

Then, a man with a wristwatch and white hair stuffed in the conch

shells of his ears pushed down the seat next to me and eased

himself into the zig-zag-patterned plushness, his knees falling open.

At intermission, this man will fling his playbill on the floor, hustle

his wife out, and huff: I can’t understand the way these people

talk. I don’t even know what they’re saying. His exit will come

as no surprise to the rest of his row because when he first sat down,

he looked at the women, then looked at me, then looked

at the women, then looked at me, and, seeing dissimilarity, in all sincerity

and smiles, he inquired, Did you bring these girls here on a field trip?

I hardened. No, just a ladies’ day at the playhouse, I said.

I felt our two rows wilt, then the house lights blacked out.

***

This detail didn’t make it into the poem, but it’s worth sharing here. When I said to him, “Nope. Just a ladies’ day at the playhouse,” he looked back at the women and noted that they were, in fact, not school-aged children. They were full-grown women, who, in some cases, were only two years younger than I was at the time. “Yes, I see now,” he said.

But he didn’t see them. He didn’t look at their faces. He saw what he thought he saw: the white teacher with the students of color on a field trip to the theater. But what can you expect from a man who walks out on an August Wilson play, admitting he doesn’t understand?

We managed to enjoy the play anyway, for no other reason than the women’s resilience in the face of that kind of invisibility. Hambone’s famous lines, “I want my ham! He gonna give me my ham!” was our mantra for many months after that.

Hambone is described in Wilson’s stage directions as follows: “He is self-contained in a world of his own. His mental condition has deteriorated to such a point that he can only say two phrases, and he repeats them idiotically over and over.” Ten years earlier, Hambone painted a fence for a white man, Lutz, who promised that he would give Hambone a ham if the job had been well done. Hambone was told to take a chicken instead. “So,” Holloway says, “[Hambone] wait over there every morning till Lutz come to open his store and he tell him he wants his ham. He ain’t got it yet.”

The young mothers understood Hambone’s plight and the profundity of “He gonna give me my ham!” They knew that the repetition of these lines was an assertion of his dignity, his humanity, and his pride in the face of those who threaten to strip them all away, whether it’s an ignorant man at the playhouse, a social worker who should have changed her line of work before burning out, or a society that sees people merely as stereotypes, women on welfare, draining the system.

In the end, Sterling, the young radical recently released from prison, gets Hambone his ham. Sterling is bleeding from his hands and his face as he lays the ham on the table in the center of the stage, a humble offering. My ham was poetry. Sterling’s ham does not reconcile the indignities Hambone suffered any more than the poems did for the women, but both are a kind of sustenance that encourage us to carry on.

In Defense of Poetry

The Haven House for Homeless Women and Children

come celebrate

with me that every day

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.

—Lucille Clifton

To you who say

poetry is a waste of ten homeless mothers’ time—

that I should correct their grammar and spelling,

spit-shine their speech so it gleams, make them sound

more like me, that I should set a bucket of Yes, Miss,

Thank You, and Whatever you say, Miss on their heads,

fill that bucket heavy, tell them how to tip-toe

to keep it steady, that I should give them something

they can truly use, like diapers, food, or boots—

I say

you’ve never seen these women lower their noses

over poetry, as if praying the rosary, as if hoping

for a lover to slip his tongue between their lips,

or sip a thin spring of water from a fountain.

Lauren Marie Schmidt is the author of three collections of poetry: Two Black Eyes and a Patch of Hair Missing; The Voodoo Doll Parade, selected for the Main Street Rag Author’s Choice Chapbook Series; and Psalms of The Dining Room, a sequence of poems about her volunteer experience at a soup kitchen in Eugene, Oregon. Her work has appeared in journals such as North American Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Rattle, Nimrod, Painted Bride Quarterly, PANK, New York Quarterly, Bellevue Literary Review, The Progressive, and others. Her awards include the So to Speak Poetry Prize, the Neil Postman Prize for Metaphor, The Janet B. McCabe Prize for Poetry, and the Bellevue Literary Review’s Vilcek Prize for Poetry. Her fourth collection, Filthy Labors, was released 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Schmidt is currently at work on a Young Adult novel.

Lauren Marie Schmidt is the author of three collections of poetry: Two Black Eyes and a Patch of Hair Missing; The Voodoo Doll Parade, selected for the Main Street Rag Author’s Choice Chapbook Series; and Psalms of The Dining Room, a sequence of poems about her volunteer experience at a soup kitchen in Eugene, Oregon. Her work has appeared in journals such as North American Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Rattle, Nimrod, Painted Bride Quarterly, PANK, New York Quarterly, Bellevue Literary Review, The Progressive, and others. Her awards include the So to Speak Poetry Prize, the Neil Postman Prize for Metaphor, The Janet B. McCabe Prize for Poetry, and the Bellevue Literary Review’s Vilcek Prize for Poetry. Her fourth collection, Filthy Labors, was released 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Schmidt is currently at work on a Young Adult novel.